Apr 24, 2017

As I said in last week’s article about Bob Harper, I am kind of playing catch up with a lot of topics, this being one of them. In late 2016, the State of Rhode Island announced publicly that on March 1 of this year, there would be a significant protocol change to their cardiac arrest protocols. Crews would be expected to remain on scene for 30 minutes prior to being transported.

Topically, I applaud Rhode Island’s Department of Health for being as public and transparent as they were about this change. Anybody who has been in the field for even a modest amount of time has been on a scene where they were asked “why aren’t you just taking them to the hospital?” In some cases, there is some merit to that. In some cases there is very little that we as paramedics and EMTs can do for a patient on a scene. Cardiac arrest is not one of those emergencies.

I saw some pushback online from some who consider themselves experts on the topic, but that’s neither here nor there. One common complaint that I saw revolved around scene safety. Obviously, scene safety trumps all. If I am coding someone in the middle of a street with an aggressive or growing crowd, I am going to think about moving. But on these calls are the exception to the rule, and on the vast majority of runs, even in the worst areas of someone’s coverage area, communication with families goes a long way.

“We are doing everything for them right here that they would get in the emergency room. It is their best chance to survive.” That’s the common statement that I have made a number of times to families of patients in cardiac arrest.

Maybe those dissenters failed to read the protocol, it states “Regardless of proximity to a receiving facility, absent concern for provider safety, or traumatic etiology for cardiac arrest, resuscitation should occur at the location the patient is found.” Emphasis is mine. Most of the write ups that I read from the online blogging community were written on or around the month of December. It is certainly possible that the state took feedback and made these changes to the protocol. If they did, kudos for listening to the people in the street. If not, then I am glad they thought the protocol out enough to insert this, and eliminate a lot of problems.

The mandate by the State of Rhode Island does raise some questions for me though. Why did they have to make a mandate like this? Why were they seeing such a prevalence of people transporting patients sooner than desired? Why did the state have to put their foot down in such a seemingly black and white fashion? Remaining on scene should be stressed, but so should a paramedic’s ability to think and make judgement calls.

I took a look at Rhode Island’s adult cardiac arrest protocol, and I must say that I am impressed. Here are a few of the highlights for me.

- “Continuous compressions and delivery of electrical therapy should take priority over other care.”

- “. . . pauses should be limited to < 5 seconds.”

- “Pre-charge the defibrillator at 1:45 sec of each duty cycles to minimize pre-shock pauses if electrical therapy is indicated.”

- “If the EtCO2 is <10 mmHg, attempt to improve CPR quality.”

It is written like something straight out of the Seattle Resuscitation Academy. It’s beautiful. The “Pearls” page goes even deeper into cardiac arrest care, going as far as to state that “Naloxone has no utility in cardiac arrest, even if secondary to opioid ingestion/overdose.” It also quotes studies about the impact of pause times on survival and advocates for vector changes and even double sequential defibrillation. It is evidence based resuscitation at its finest. With one exception.

The endpoint of the resuscitation regardless of the patient’s condition after 30 minutes is “transport.” Where is the cessation protocols? We have given our medics the power to work their arrests in an ER-style “code them where they are found, and code them well” manner, but then we require them to move them, do inadequate CPR in the back of an ambulance to the hospital, and deliver a dead patient, now probably more than 45 minutes or more post-arrest to a doctor who can then say “yes, they’re dead.” Rhode Island has given their paramedics a lot of responsibility, why has this been left out?

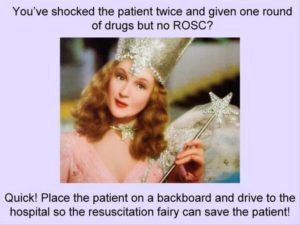

In 2012, Tom Bouthillet gave us the Resuscitation Fairy. That concept has not changed. There is no magical in hospital intervention that is going to save our patient’s lives. Caring for a patient in cardiac arrest is just as much mental as it is physical. Steps need to be planned out and treatments in those more complicated arrests need to be thought out. This need is even more significant in post-resuscitation care, something that we will talk about in a later article. Rhode Island thinks so too. They mandate the palpation of a pulse for 10 minutes post-arrest with directed therapy to airway management and cardiac stability. Well done.

From all indications, this new protocol was instituted statewide on March 1. Now, here we are almost two months later. While I am sure that there were some growing pains, and resistance to change, with almost 60 days of data, I wonder what they have seen in terms of survival rates.