Oct 20, 2014

In light of all of the media attention being made about the most recent Ebola outbreak that has now spread to the United States, I thought it would be beneficial to put together a three part series about the Ebola Virus. In this first part, we will talk about the history of the disease to help us better understand where it came from, and the impact that it has had over the past nearly forty years. Part two will talk about what you as an EMS responder needs to know about the disease, and in the final part we will talk about things that you should think about after dealing with a potentially infected patient.

The Discovery of Ebola

Ebola was discovered after its first documented outbreak in 1976 which occurred from June through November in Nzara, South Sudan. The World Health Organization (WHO) knew that they were dealing with some sort of hemmoragic fever but did not realize that it would be as deadly as the Ebola virus turned out to be.

The first documented case of Ebola was discovered on June 27th when a Sudanese store owner became symptomatic and died just nine days later. In total, the first outbreak of Ebola infected 284 people and resulted in 151 deaths.

The disease was named nearly six months later for the Ebola River which is located near the location of the first documented outbreak. With the disease becoming more publicized thanks to the WHO and Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) involvement, an additional 318 cases were identified with 280 of them proving to be fatal. The two departments undertook a combined effort to contain the disease and were eventually successful in doing so. Interestingly enough, one of the most effective strategies that was used to contain the outbreak was the advocating of the discontinuation of reusing needles by local medical providers.

Over the next nearly twenty years the disease stayed out of the headlines and off the radar of the CDC and WHO then in 1995, the second major outbreak of Ebola occurred in Congo infecting 315 people and killing 254. Five years later, another outbreak occurred in Uganda claiming an additional 224 lives. 2003 saw the next major outbreak, this one again occurring in the Congo, which had a 90% mortality rate, killing 128 of 143 infected individuals. From 2003 until 2014, there were a few smaller outbreaks each with less than 150 documented patients. Then, in 2014 the current outbreak occurring in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone began.

The current outbreak taking place in West Africa is the largest documented outbreak of the disease on record. As of October 15, 2014 there have been 8,998 suspected cases of Ebola with 4,493 documented deaths which many in the WHO think is a conservative estimate. The fallout from the West African outbreak has resulted in the public health system virtually grinding to a halt. One statistic that has not and probably cannot be calculated is the number of people of have indirectly lost their lives because of the virus’s impact on the system.

What Is it?

It has been well publicized that Ebola is in fact a virus. The virus itself is carried by fruit bats which are not affected, and able to spread it freely. When a human or other animal comes in contact with an infected bat, either dead or alive, they are at risk for infection themselves. For example, the removal of deceased animals, or even the consumption of an infected animal could put a person at serious risk for contracting Ebola.

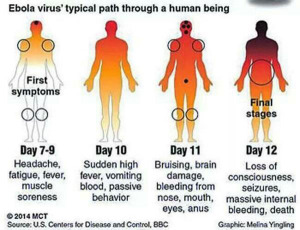

Ebola targets the inner linings of blood vessels such as macrophages, monocytes, and liver cells. The protein created in the attack disguises the Ebola virus from certain types of white blood cells allowing the virus to use those cells to spread throughout the body allowing it to begin attacking the lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and spleen to name just a few. The body responds just as it would to any other infection with a fever and inflammation. Because of the damage that has already been done to the body by the virus, specifically to the liver, the body’s clotting factors are affected causing uncontrolled internal and occasionally external hemorrhage. Death most often occurs because the patient is volume depleted and hypotensive due to the massive hemorrhage.

Diagnosing Ebola

Diagnosis of Ebola comes from a combination of history gathering for a person’s travel and work history as well as blood tests to look proteins in the patient’s blood early in infection, or searching for antibodies late in the infection. Ebola shares its symptoms with many different types of hemorrhagic fevers as well as a number of non-infectious diseases which can make its identification difficult and time consuming especially since many of these diseases require prompt treatment and intervention.

Unfortunately, there is currently no vaccine for the Ebola virus. In the next part of this series we will talk about the signs and symptoms associated with the Ebola virus and the treatment, or rather lack there of, for it.

1. About Ebola Disease – CDC October 2014

2. Ebola Virus Infection Author: John W King MD October 2014

3. Ebola Outbreak Confirmed in Congo Author: Reuters and NewScientist.com staff September 2007

4. WHO Raises Global Alarm over Ebola Outbreak Author: CBS/AP August 2014